On July 6th, 2024, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, opened its very first full exhibition of works by famed surrealist Salvador Dalí. “Dalí: Disruption and Devotion” juxtaposes nearly 30 works from across Dalí’s artistic career with European masters. From smaller prints to larger oil paintings, the exhibit from the MFA creates a fascinating dialogue that reveals the inspirations for Dalí’s approaches. The show closed on December 1st, 2024.

Salvador Dalí, Nature Morte Vivante (Still Life-Fast Moving), 1956

The exhibit winds between rooms, slowly revealing another aspect of an era or approach by Dalí behind every corner. The decision to juxtapose artworks from European masters with Dalí’s work contextualized his work in a way I personally had never seen before. It made me realize how little of Dalí and artistic influences I knew. From Spanish masters such as Velázquez to El Greco, Dalí’s observation and deconstruction of their works is evident in the conversation between the old masters and his modernist. At first, upon entering the show, I was confused by the placing of older masters along these works. However, I quickly understood that the ways in which these works converse and relate to one another are extraordinary. This is no better exemplified than the pairing of Velázquez’s Infanta Maria Theresa (1653) with Dalí’s Velázquez Painting the Infanta Marguerita with the Lights and Shadows of His Own Glory (1958). Not only does it reference Velázquez’s works, but it illustrates how Dalí approaches his influences. As the title of the show hints, this painting is the perfect example of Dalí’s devotion to Velázquez, as well as how he distorted it. This exhibit also masterfully displays the evolution of Dalí’s artistic skills.

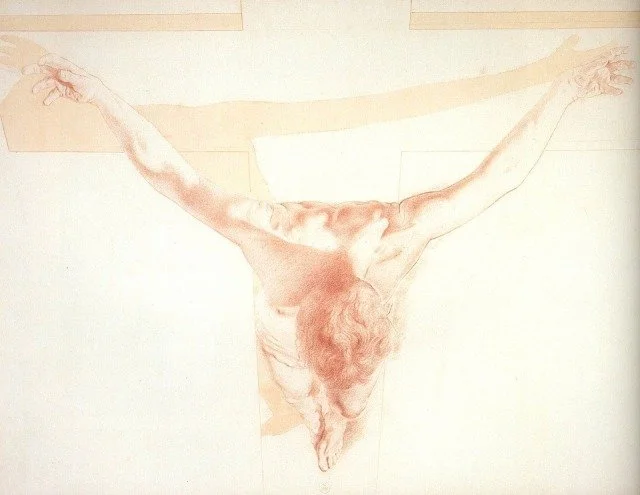

Salvador Dalí, A preparatory drawing for Christ of St. John of the Cross (Christ On The Cross From Top Perspective)

The maze-like space continues this unraveling of Dalí, revealing more and more of his psyche. With every work accompanied by a European master, no wall in this space does not illicit conversation. A tremendous accomplishment is that there is no piece that feels under-considered. An expected revelation for me was Dalí’s own religiosity. His preparatory drawing for Christ of St. John of the Cross was on display and revealed a deeply sympathetic side of Dalí and his relationship with Christ. The soft red drawing is a silent highlight of the exhibition. The section dedicated directly to his religious connections culminates with his larger-than-life oil painting, The Ecumenical Council. In Dalíesque fashion, the curators even included a little square cut out of the wall to view this painting from the proceeding room.

Salvador Dalí, The Ecumenical Council, 1960

The exhibit reaches its ultimate conclusion in the final room with paintings that resemble those created in the style of The Persistence of Memory. At first, I pondered if the curators had just been unable to get his arguably most famous work. However, regardless of whether they had tried, the show is stronger without it. The presence of the painting would have overshadowed everything else. The strength of the exhibit is how the curators managed to unravel the artist and undermine expectations. Prior to this, I would never have considered myself a major Dalí fan. However, this collection of works crafted an exciting and illuminating conversation around Dalí and his artworks.